Bent little finger: The myth

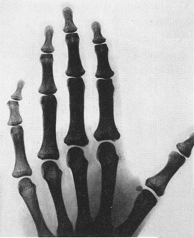

Some people's little fingers bend in towards the ring fingers (B), while in other people they are straight (S). The myth is that little fingers can be clearly divided into two categories, bent and straight, and that the trait is controlled by one gene with two alleles, with the allele for B being dominant. Neither part of the myth is true.

The reality

Bent little finger as a character

The technical name for a little finger that bends in towards the ring finger is clinodactyly. When the little finger bends in towards the palm and can't be straightened out, it is known as streblomicrodactyly, streblodactyly or camptodactyly.

Little fingers range from perfectly straight to bending inwards at a sharp angle. It is not clear whether fingers fall into two discrete categories or there is a continuous range of pinky angle. Hersh et al. (1953) said that bent little fingers bend inward at an angle of 15 to 30 degrees. They found that only 4 out of a sample of 4,304 people had what they considered to be bent little fingers. Marden et al. (1964) identified about 1% of healthy newborns as having bent little fingers.

Family studies

Hersh et al. (1953) identified 51 families in which one or more children had bent little fingers. In 47 of the families, one parent had bent little fingers and the other had straight. Hersh et al. (1953) concluded that bent little finger was caused by a single dominant allele, but the four families in which both parents of a B child were S are inconsistent with this.

Dutta (1965) found two extended families with bent little fingers. Six children of S x S parents were all S, while 22 out of 34 children of B x S parents were B. This fits the model of bent little finger being caused by a single dominant allele, but the number of families is very small. Leung and Kao (2003) found one more extended family in which bent little fingers were common; they concluded that it fit the model of B caused by a dominant allele, but the data also fit a model in which it is recessive.

Conclusion

If only extremely bent little fingers are considered, as done by Hersh et al. (1953), then the bent little finger trait is too rare to be useful for illustrating basic genetics in classrooms. If fingers with a more moderate bend are counted, then there is no clear dividing line between bent and straight, plus no evidence that the trait is genetic. In either case, you should not use bent little finger to demonstrate basic genetics.

References

Dutta, P. 1965. Inheritance of radially curved little finger. Acta Genetica et Statistica Medica 15: 70-76.

Hersh, A.H., F. DeMarinis, and R.M. Stecher. 1953. On the inheritance and development of clinodactyly. American Journal of Human Genetics 5: 257-268.

Leung, A.K.C, and Kao, C.P. 2003. Familial clinodactyly of the fifth finger. Journal of the National Medical Association 95: 1198-1200.

Marden, P.M., Smith, D.W., and McDonald, M.J. 1964. Congenital anomalies in the newborn infant, including minor variations: a study of 4,412 babies by surface examination for anomalies and buccal smear for sex chromatin. Journal of Pediatrics 64: 357-371.

Return to John McDonald's home page

This page was last revised December 8, 2011. Its address is http://udel.edu/~mcdonald/mythbentpinkie.html. It may be cited as pp. 20-21 in: McDonald, J.H. 2011. Myths of Human Genetics. Sparky House Publishing, Baltimore, Maryland.

©2011 by John H. McDonald. You can probably do what you want with this content; see the permissions page for details.