Beeturia: The myth

After some people eat beets, their urine turns red, a harmless condition called beeturia or betaninuria. Because this looks like blood in the urine, someone who doesn't know it is caused by beets can become alarmed and go see a doctor. Other people have normal-looking yellow urine after they eat beets. The myth is that beeturia is caused by a single gene with two alleles, with the allele for beeturia being recessive.

The reality

Beeturia as a character

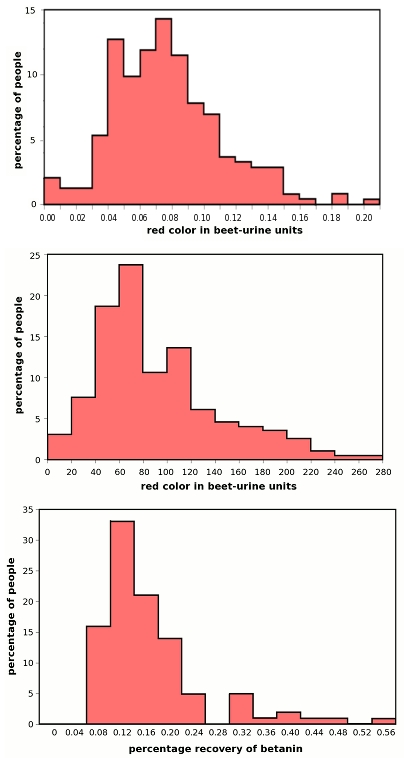

In early studies of beeturia (Allison and McWhirter 1956, Saldanha et al. 1960, Saldanha et al. 1962, Watson et al. 1963), people ate beets and then were classified as beeturic or non-beeturic based on the appearance of the urine. In general, people were classified as beeturic if there was any detectable redness in their urine. Forrai et al. (1968, 1982) measured the red color in urine with a photometer set to 530 nm, with the absorbance at the yellow wavelength of 660 nm subtracted to give "beet urine units." They found a broad distribution, but no separation into excretors and non-excretors, in a sample of 244 children (Forrai et al. 1968) and 198 twins (Forrai et al. 1982). Pearcy et al. (1991) conducted a similar study and came to the same conclusion, but they do not give their data. Watts et al. (1993) also found a distribution that was skewed but not bimodal.

|

| Percentage of people with different amounts of betanine in their urine after eating beets. Top, data from Forrai et al. (1968); middle, data from Forrai et al. (1982); bottom, data from Watts et al. (1993). |

Watson et al. (1963) and Tunnessen et al. (1969) found that beeturia was more common in people with iron deficiency, but Forrai et al. (1971) did not find a relationship between betanin and blood iron levels. Eastwood and Nyhlin (1995) gave non-beeturic subjects a mixture of betalaine and oxalic acid, and they became beeturic. Their interpretation was that the oxalic acid prevented betalaine from being decolorized in the stomach and colon, so that the variation among individuals in the redness of beet urine resulted from varying amounts of oxalic acid in the digestive system. They also found that vinegar-pickled beets caused more people to be beeturic than boiled beets, consistent with the role of acid in causing beeturia.

Family studies

Allison and McWhirter (1956) visually divided people into beeturic (B) and non-beeturic (NB) and looked at a number of families, with the following results:

| Parents | NB offspring | B offspring |

|---|---|---|

| NB x NB | 14 | 2 |

| NB x B | 2 | 2 |

| B x B | 0 | 6 |

Because all six offspring of B x B matings were beeturic, they concluded that beeturia was caused by a recessive allele.

Saldanha et al. (1962) looked at a larger number of families:

| Parents | NB offspring | B offspring |

|---|---|---|

| NB x NB | 18 | 4 |

| NB x B | 15 | 19 |

| B x B | 17 | 38 |

The 17 non-beeturic offspring of B x B matings do not fit the idea that beeturia is caused by a recessive allele. Saldanha et al. (1962) considered people with "very weak" amounts of red pigment in their urine as beeturic, while Allison and McWhirter (1956) only counted people who were "distinctly positive" for beeturia.

Twin studies

Forrai et al. (1982) fed pairs of twins uniform amounts of beet juice and measured the red pigment in their urine, rather than just classifying them as beeturic or non-beeturic. They found that monozygotic twins were not more similar to each other than dizygotic twins. If the amount of red pigment was determined by genetic variation, monozygotic twins should be more similar to each other, so this suggests that beeturia is not strongly affected by genetics.

Conclusion

The careful measurements of Forrai et al. (1982) and Watts et al. (1993) show that people cannot be divided into two distinct categories, beeturic and non-beeturic; instead, there is a continuous range of variation in the redness of urine after eating beets. The twin study of Forrai et al. (1982) suggests that this variation is not strongly determined by genetics. Beeturia is not a simple one-locus, two-allele trait.

References

Allison, A. C., and K. G. McWhirter. 1956. Two unifactorial characters for which man is polymorphic. Nature 178: 748-749.

Eastwood, M. A., and H. Nyhlin. 1995. Beeturia and colonic oxalic acid. Quarterly Journal of Medicine 88: 711-717.

Forrai, G., D. Vágújfalvi, and P. Bölcskey. 1968. Betaninuria in childhood. Acta Paediatrica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 9: 43-51.

Forrai, G., D. Vágújfalvi, J. Lutter, E. Benedek, and E. Soós. 1971. No simple association between betanin excretion and iron deficiency. Folia Haematologica 95: 245-248.

Forrai, G., G. Bankovi, and D. Vágújfalvi. 1982. Betaninuria: a genetic trait? Acta Physiologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 59: 265-282.

Geldmacher-von Mallinckrodt, M., M. T. Aiello, and M. V. Aiello. 1967. Quantitative erfassung und klinische bedeutung der betaninurie. Zeitschrift für Klinische Chemie und Klinische Biochemie 5: 264-270.

Pearcy, R. M., S. C. Mitchell, and R. L. Smith. 1991. Beetroot and red urine. Biochemical Society Transactions 20: 225.

Saldanha, P. H., L. E. Magalhães, and W. A. Horta. 1960. Race differences in the ability to excrete beetroot pigment (betanin). Nature 187: 806.

Saldanha, P. H., O. Frota-Pessoa, and L. I. S. Peixoto. 1962. On the genetics of betanin excretion. Journal of Heredity 53: 296-298.

Tunnessen, W. W., C. Smith, and F. A. Oski. 1969. Beeturia. American Journal of Diseases of Children 117: 424-426.

Watson, W. C., R. G. Luke, and J. A. Inall. 1963. Beeturia: its incidence and a clue to its mechanism. British Medical Journal 2: 971-973.

Watts, A. R., M. S. Lennard, S. L. Mason, G. T. Tucker, and H. F. 1993. Beeturia and the biological fate of beetroot pigments. Pharmacogenetics 3: 302-311.

Return to John McDonald's home page

This page was last revised December 8, 2011. Its address is http://udel.edu/~mcdonald/mythbeeturia.html. It may be cited as pp. 17-19 in: McDonald, J.H. 2011. Myths of Human Genetics. Sparky House Publishing, Baltimore, Maryland.

©2011 by John H. McDonald. You can probably do what you want with this content; see the permissions page for details.