Crucial conversations

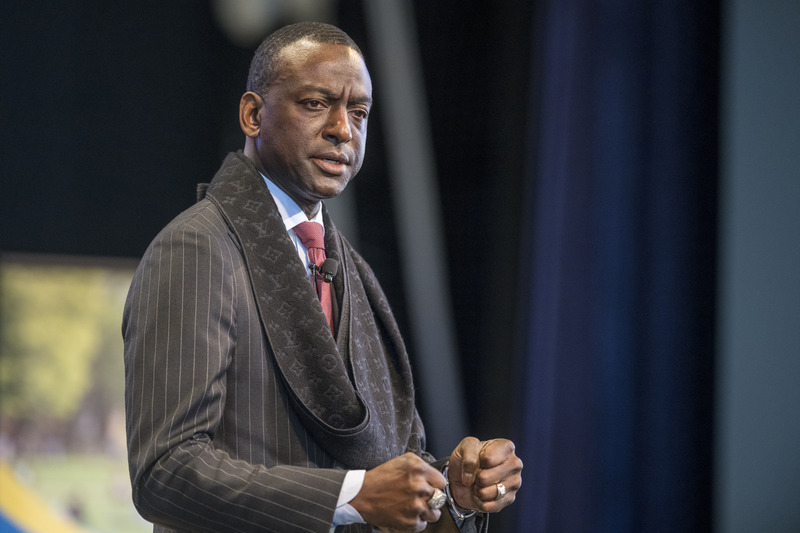

Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson March 15, 2024

One of the Central Park ‘Exonerated Five’ shares his story of finding hope and using his platform to advocate for reform

Yusef Salaam can’t say what his life would have been like had he not gone to New York City’s Central Park on the evening of April 19, 1989, calling the question the “great unknown.” Salaam describes himself then as a shy, creative 15-year-old interested in architecture and graphic design. He had no idea that his childhood would end that day.

Salaam and four other Black and Latino teens, Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana and Korey Wise, were convicted in the brutal attack and rape of a white woman, Trisha Meili, who was jogging in the park that evening almost 35 years ago.

At the time, they were dubbed the “Central Park Five,” and politicians like Pat Buchanan called for their execution. Today, the preferred moniker is the “Exonerated Five,” and the case is one of the country’s most infamous instances of wrongful conviction.

Salaam visited UD on Tuesday, March 12, to share his journey from being wrongfully convicted of a brutal crime at just 15 years old to building a life of purpose as a motivational speaker, activist for criminal justice reform and recently elected member of the New York City Council. In these roles, Salaam works to improve the system that treated him so unjustly.

“People who get exonerated and let go — they don’t get let go with services. They don’t get let go with support,” he said. “Those of us who know what’s needed have to speak that truth to the system that wronged them. You came into the prison at 16 and you’re leaving a grown man. You don’t have the toolkit to know how to navigate things.”

Crucial conversations

The event was the second annual Ida B. Well lecture, an initiative launched by the Department of Women and Gender Studies to bring the campus community together in dialogue about race and injustice. The series is supported by a grant from the Mellon Foundation’s Affirming Multivocal Humanities program and by the College of Arts and Sciences.

Angela Hattery, professor of women and gender studies and co-director of the Center for the Study and Prevention of Gender-Based Violence, welcomed the audience, saying, “These conversations are both difficult and deeply necessary. This event provides a space for us to critically engage the myriad ways in which the criminal legal system destroys the lives of Black men in this country.”

Hattery offered stark statistics for the audience to consider: Black men make up the majority of cases in which people are wrongfully convicted, and exonerated men like Salaam have collectively spent more than 25,000 years in prison, including thousands of years in solitary confinement.

On the day after Meili’s attack, police interrogated the teens for hours without legal counsel, ultimately coercing false confessions from the frightened, exhausted boys. All five were convicted, despite the lack of physical evidence and all of them recanting their confessions almost immediately. They served between seven and 15 years before being exonerated after a different man, Matias Reyes, confessed in 2002.

Salaam told the audience that had police expanded the initial investigation, the real culprit could have been apprehended at the time.

“It’s from his own mouth,” Salaam said. “[Reyes] said, ‘I was leaving the park that night, and the police officers put their flashlights right in my face.’ He said that had they shone their flashlight on his whole body they would see that he's bloodied from the waist down.”

Finding hope

Despite what he endured from the criminal legal system, Salaam told the audience that an officer helped him survive his time in prison.

Six months into his sentence, a guard walked up to Salaam and asked him a simple question: Who are you?

Salaam said his name and why he was there, but the officer asked again: You don’t belong here. Who are you?

“I realized that I didn’t know who I was,” Salaam said. “I realized that when I said my name, I didn’t know what the name meant.”

The interaction inspired Salaam to engage in self reflection. He began writing poetry as a way to process his experiences. After his release, Salaam moved to the Atlanta area and served on the board of the Innocence Project, an organization that works to exonerate wrongly convicted individuals. He married and became a father and motivational speaker. In 2022 he returned to New York to campaign for the City Council, running on a platform of police reform.

Salaam also continued writing, and in 2021 he released his memoir, Better, Not Bitter: Living on Purpose in the Pursuit of Racial Justice.

Salaam smiled, telling the audience that it might just be the first memoir, as he will continue to advocate for reform as a councilman.

“The criminal justice system has to get it right,” he said. “They want you to believe that the Central Park Jogger case is an anomaly. That this is not an American issue.”

Salaam said race disproportionately impacts people of color facing prosecution.

“But when you look at the amount of times they’ve gotten it wrong, it’s not a mistake,” he said. “Systemically what happens, and this is really the crux of the matter, they are trying to create a criminal class that only sees prison and no other way.”

Sov Im, a senior women and gender studies major who attended the event, said that she hears horrific stories of corruption in many of her classes, but hearing how Salaam has changed his life after being released gives her hope.

Agents of change

Several students have engaged in a mini-curriculum this semester to explore the history and impact of wrongful conviction, and many were in attendance to hear Salaam’s story first-hand and ask him questions about his experiences and hopes for a better America.

“Hearing from people like Dr. Salaam, who have gone through unimaginable hardship, is inspiring, especially witnessing the progression of self to the point of success that he has achieved,” said senior sociology and women and gender studies major Bailey Coco.

Coco asked Salaam how his experience as an exoneree shaped his perceptions of the criminal legal system. He relayed a story of meeting a 13-year-old girl at a speaking engagement who told him that she wanted to become a police officer and asked him for advice. At first taken aback, Salaam chose to encourage the young girl.

“I realized I wasn’t talking to a cop. I was talking to the future of what policing could be, and I gave her my best stuff about the impact that I’ve seen, about the words ‘to serve and protect.’ I didn’t talk about the bad stuff because I know that there are hundreds if not thousands of good cops,” he said.

Salaam told the audience, and especially the students, to envision their future and reverse engineer to achieve their goals, and not to let fear hold them back.

“When things don’t pass the test, reexamine the road that you’re going down,” he said. “There’s so much that we have to do. It doesn’t come from the current places that we’re in. It’s going to come from you all. The future that you all hold to be the future scientists, future doctors, future educators. You are actually the future of everything.”

This was the main takeaway of the evening for Danielle Linekin, a senior philosophy and women and gender studies double major.

“I left Dr. Salaam’s lecture feeling inspired, capable and ready to take action so the criminal justice system cannot do to someone else what it did to Yusef Salaam,” Linekin said.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website