Scientific mentorship

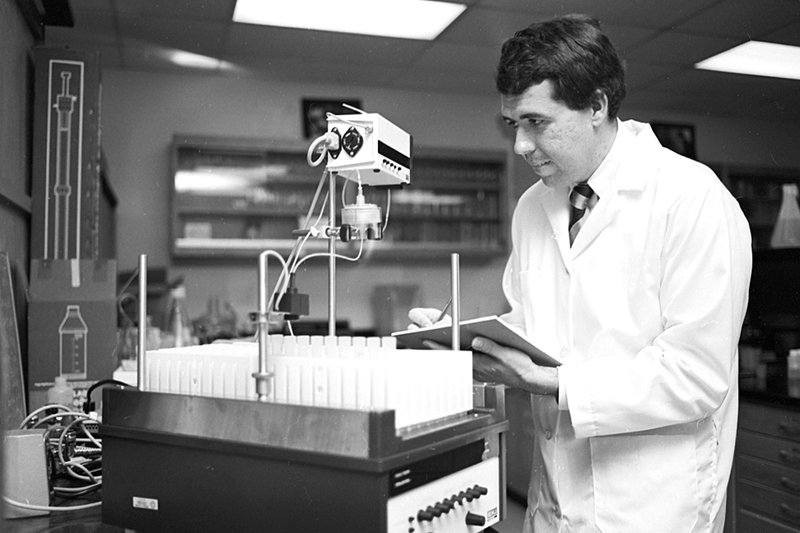

Photos by Evan Krape and Kathy F. Atkinson and courtesy of University Archives June 12, 2024

UD plant and soil sciences alumni say mentorship was a hallmark of Don Sparks’ illustrious UD career

Maria (Sadusky) Pautler was finishing up her master’s degree in soil chemistry at the University of Delaware in 1987. An optimist who wanted to help solve world hunger, she found herself considering what to do next. One day, she noticed an environmental contract job opening with the U.S. Army in Maryland.

Pautler started to put together her résumé. But before she even mailed in her job application, she was invited in for an interview.

A letter of support from renowned University of Delaware soil scientist Donald Sparks landed in the hiring committee’s lap and immediately impressed.

“I just remember asking him, ‘What did you put in that letter? I didn’t even send my CV down yet,’” Pautler said. “I ended up getting that job.”

Pautler, who returned to UD in 1996 to work for the Department of Plant and Soil Sciences as a research associate and program coordinator before retiring in 2022, is among many students who have come to UD to do research alongside Sparks, the Unidel S. Hallock du Pont Chair in Soil and Environmental Chemistry, founding director of the Delaware Environmental Institute and Francis Alison Professor. Pautler’s story speaks to the kind of professor Sparks is — one who always looked out for his students and saw their talents, sometimes before they did.

This month, Sparks retires after a 45-year career at UD. One of the world’s top researchers in environmental soil science, Sparks built UD Plant and Soil Sciences into a renowned department. His legacy is far-reaching across the U.S. and the world. Over the years, Sparks mentored his students with kindness and generosity, treating them like family and forming an academic family tree. Besides helping them form connections across the industry, Sparks propelled his students to success in careers across academia, the private sector, and governmental agencies.

A four-decade-long career

Sparks, a born and bred Kentuckian, graduated from the University of Kentucky in 1975 with a bachelor of science degree in agronomy. He went on to get his master’s in soil science from the same university a year later. In 1979, Sparks completed his Ph.D. in soil science at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Immediately after graduating with his doctorate degree, Sparks joined UD, where he has spent his whole career.

Sparks focused the early years of his career researching nutrients phosphorus and potassium in soils. In the late 1980s, his research pivoted to examining heavy metals nickel, arsenic and chromium, and the negative impacts these toxins can have on soils and water quality.

“Our goal was to try and understand how these different elements interacted with soils,” Sparks said. “We did a lot of work on the kinetics of reactions — how rapidly these processes occur — because that determines what their fate will be in the environment.”

In the early 1990s, Sparks’ lab started using a type of particle accelerator called a synchrotron to produce bright light sources that help study soil-chemical reactions, using it to determine, for example, how nickel could bind to a soil’s surface. The technique helps scientists make predictions about how likely a contaminant could infiltrate water supplies or how toxic it is to plants.

“That opened up a whole new avenue of research,” Sparks said. “I was able to train a lot of students using that technique. And I think it was very instrumental in them getting placed.”

Sparks was also instrumental in launching the Delaware Environmental Institute in 2009, where he served as director for 13 years, uniting scientists through research to tackle climate change.

Sparks has won numerous honors and awards for his work in soil sciences. Among them, he has been recognized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Society of Agronomy, the Soil Science Society of America and the International Union of Soil Sciences. In 1996, Sparks was the recipient of the University of Delaware Francis Alison Award, UD’s highest honor for a faculty member. And at UD’s 2024 commencement ceremony, the University bestowed Sparks with an honorary degree. This high accolade is reserved for individuals who reflect, in their personal and professional achievements, the University’s mission and who serve as exemplars for UD’s students, alumni, the University community and the world.

Sparks not only has made numerous contributions to UD as an academic, but he is also a generous donor. His philanthropic investment includes the establishment of the Donald and Joy Sparks Graduate Fellowship in Soil Science and the Joy Gooden Sparks Scholarship, named after his late wife and which supports 4-H members who enroll in CANR. Additionally, Sparks established the Donald L. Sparks Distinguished Lectureship in Soil and Environmental Sciences, which brings renowned thought leaders from across multidisciplinary backgrounds to UD to share insight and research around the latest topics in soil and environmental sciences.

A devoted mentor

Being a professor and taking on the role of a mentor go together hand in hand. That is the Don Sparks decree.

“As a mentor, you try to make sure you train students so that they’re going to be good to go out in the world, and they’re going to have a great career,” Sparks said. “I've always tried to instill in my students things like being humble, being honest, being able to articulate their ideas and have good oral communication, good writing communication, giving them opportunities to travel for meetings abroad, and making sure they get the very best training because it’s a very competitive world.”

At a given time, there are not many academic positions available in soil sciences, but Sparks has watched proudly as 26 of his students over the years have gone on to land these positions.

Over the course of his career, Sparks has mentored 65 graduate students, 35 postdoctoral researchers and approximately 30 visiting scholars and professors. When Sparks would interview students for his lab, he looked for those who were academically strong, with a solid work ethic and good people skills.

As a mentor, Sparks took a very personable approach to making sure each of his students thrived.

“I met with each of them,” Sparks said. “I always had an open door.”

Sparks would even hold group meetings with his lab a couple times a month to help prepare students for professional conferences and meetings. He always tried to instill in his students to know their audience. Help an audience understand the research. To discuss their research without the jargon, as if they were sharing it with a sibling or a neighbor.

Sparks’ alumni excel

The soil science community is small and tight-knit, so Sparks’ alumni formed an enduring family-like bond.

“The Sparks family is very warm and welcoming,” said Jason Fischel, a remedial project manager at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and UD Class of 2018 doctoral graduate. “Being part of that means that people are helpful and go above and beyond what they normally would do because we all share that common connection.”

Sparks taught Fischel lab skills and how to scientifically dissect a problem. Fischel’s younger brother, Matt, followed in his footsteps; he wanted to work with Sparks after meeting him at a UD Plant and Soil Science Exploration Day in high school.

Matt Fischel, a research chemist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service and 2019 UD doctoral graduate, said Sparks cultivated students by giving them freedom while also serving as a support system.

“He was there to help if you needed help,” Matt Fischel said. “But his style of leadership is giving you the freedom to learn, work with others and take risks in order to do impactful science, but also as a graduate student learn how to think and conduct science in a meaningful way.”

Ryan Tappero, a 2008 doctoral graduate from Sparks’ environmental soil chemistry program and now a scientist at Brookhaven National Laboratory, recalls joining the Sparks lab excited to perform research at the synchrotron with Sparks.

“He was really a forefront leader in bringing synchrotron-based X-ray spectroscopy and imaging techniques to the soil and environmental science community at large,” said Tappero, who is also an adjunct faculty member with the UD Department of Plant and Soil Sciences. “It’s an important part of his history and an important part of his contributions to soil science and soil chemistry.”

Pautler, the Sparks graduate who got an interview for an environmental contract job before she even sent in her resume, admired Sparks for the ways he always promoted his students and helped them get recognition in the soil science field.

“Dr. Sparks instilled a good work ethic in the members of his lab,” Pautler said. “That, along with witnessing his fair treatment of myself and others, is something I tried to emulate throughout my career.”

Jen Seiter, the technical director for civil works, environmental engineering and sciences at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineer Research and Development Center, graduated UD with a Ph.D. in 2009. Seiter valued Sparks’ mentorship and his warm and inviting personality. She never felt intimidated by him despite his high standing in the soil sciences and research community.

One of the most important things she took away from Sparks’ lab was his motto, “work hard, play hard.”

“That is my motto to this day with my family and team at work,” Seiter said. “I take pride in what I do and work really hard. But I also make sure to take time and enjoy life as well and spend time with family and the people I care about.”

What makes a good mentor?

Brandon Lafferty graduated from Sparks’ research group with a doctorate degree in 2010. He’s now the deputy director of the Environmental Laboratory at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineer Research and Development Center, working in the same building as Seiter.

In his role with the U.S. Army as well as his position as an adjunct professor with Texas A&M University, Lafferty mentors scientists, engineers and administrative professionals.

“Dr. Sparks talked to us and to me specifically a lot about understanding your position in an organization, understanding your value to the organization, and understanding how you need to understand yourself as much as you need to understand the work that you’re doing,” Lafferty said. “He treated us as much as peers and colleagues and almost like family members as he treated us like graduate students.”

Not only students looked up to Sparks. Professors in UD’s Department of Plant and Soil Sciences held him in high regard as well.

Sparks’ reputation got UD noticed by the international soil science community. Yan Jin, Edward and Elizabeth Rosenberg Professor of Plant and Soil Sciences, said people would immediately associate her with Sparks when she shared her UD affiliation at professional conferences.

“Don almost single-handedly put UD’s soil science program on the world map,” Jin said.

Soil science today

As Sparks prepares for retirement, he acknowledges that the soil science field has changed a lot.

Though he began his career focused on soil contaminants such as arsenic, a lot of emphasis on soils today is about keeping them covered to prevent erosion and keeping carbon released from plants’ process of photosynthesis stored in the soils to help fight climate change rather than that carbon contributing to it once it’s released into the atmosphere.

Sparks focused the last stretch of his career on studying permafrost — frozen soils — from Alaska. He mentored two graduate students and three postdocs on this project, collaborating with the U.S. Army’s Engineer Research and Development Center and its Permafrost Tunnel Research Facility in Fox, Alaska.

“These frozen soils have huge amounts of carbon that they’re storing,” Sparks said. “As temperatures increase and as we get more melting of these permafrost soils, there are all sorts of questions on what’s going to happen to the carbon: Is it going to go up into the atmosphere? Is it going to go into the water?”

Sparks said some of the world’s biggest challenges — climate change, food insecurity, salinity and desertification — are all intertwined, and each involves soil to some degree. That means there’s plenty of room for newcomers to the field.

“It’s certainly one of the great times to be in soil science,” Sparks said.

As Sparks looks back on his 45-year career filled with meaningful research, high honors and recognitions, he says the highlight has been mentoring all of his students and watching them move on into their own successful careers.

“Twenty years from now, or when I’m gone, people are probably not going to remember the awards that I got, but they’re probably going to say, ‘This was a student that he trained and has gone on to do successful things,’” Sparks said. “To me, that’s the legacy I’m most proud of.”

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at mediarelations@udel.edu or visit the Media Relations website