Hormones and metabolism

Illustration by Jeffrey C. Chase October 12, 2023

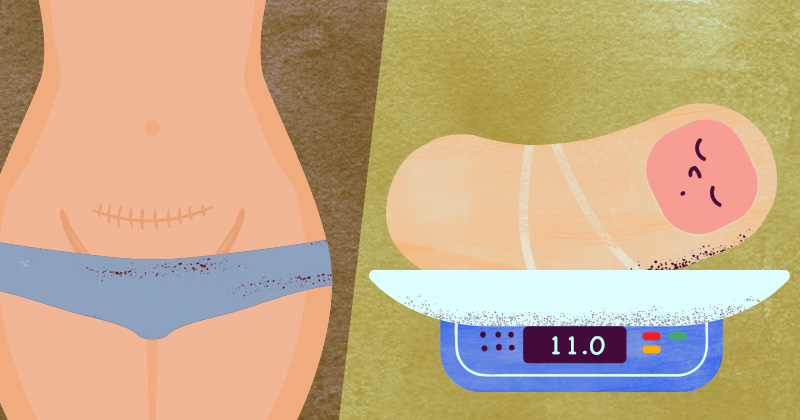

UD’s William Kenkel explores connection between cesarean section and childhood obesity

Worldwide, obesity has tripled since 1975, according to the World Health Organization. This includes an astounding 39 million children under age 5 who were considered overweight or obese in 2020.

These statistics concern William Kenkel, assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Delaware. He studies birth hormones known to be important in early life, such as oxytocin and vasopressin, which also serve important roles in metabolism. His previous work focused on the role of birth experience in development.

Now, Kenkel has received a five-year, $1.5 million grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to explore whether there are metabolic reasons that children born via cesarean section (C-section) are up to 55% more likely to experience childhood obesity.

“There is this fascinating correlation in the human literature that birth via C-section is associated with a 30 to 50% increase in childhood obesity,” Kenkel said. “This seems to be independent of mom’s weight, breastfeeding — even antibiotics. People have wondered about this through the lens of the microbiome before. I want to look at this association through the lens of hormones.”

Hormonal connections and clues

Kenkel explained that the birth process sets off a tremendous sort of fireworks in the endocrine system, where many different hormone systems are firing at their maximum.

“It’s where you see one of the highest levels of vasopressin, a hormone previously thought only to occur at high levels during cases of blood poisoning,” he said. “It turns out if you're a happy newborn baby, you will exceed those levels. So, it is a wild point of life, in terms of hormones.”

During this sensitive period, even small, short manipulations can alter the developmental trajectory, resulting in differences that linger into adulthood. Individuals delivered via cesarean section are known to experience lower levels of the birth hormones oxytocin and vasopressin, which Kenkel theorizes may contribute to why this population seems prone to childhood obesity. These hormones are highest with vaginal delivery, then emergency cesarean and lowest with scheduled cesarean delivery. By contrast, the risk for obesity follows the reverse, suggesting an important connection.

This made Kenkel wonder if delivery via C-section plays a role in priming an individual for obesity. It’s an important question, given that one in three deliveries in the United States are by C-section. Globally, this number is higher in some countries, like Brazil or China.

It’s a change in focus for the principal investigator, but one he views as an exciting opportunity to create new data in this research area. Kenkel has long studied the hormones present at birth, such as oxytocin, for their role in helping moms and babies bond. But these same hormones also serve important roles in metabolism. For example, Kenkel explained that recent studies in the literature support the idea that oxytocin can suppress appetite and help some individuals lose weight.

The brain is sensitive to these birth hormones around the time of delivery, helping infants transition from the intrauterine environment to the outside world. When they are working correctly, these hormones help coordinate important activities, such as breathing, eating and temperature regulation.

To better understand if there is a long-lasting role for these birth hormones following cesarean delivery, in terms of obesity, Kenkel has enlisted the help of collaborator J. Ernie Blevins, an expert on the hormonal regulation of metabolism from the University of Washington.

“If we find that C-section does drive childhood obesity, it doesn’t mean that women will stop having them. There are very valid medical reasons for having a C-section,” Kenkel said. “But if there are ways to improve C-sections, say, to provide hormones that mother or baby would have released during vaginal birth to make the experience more naturalistic for the infant and avert these negative consequences, it would be good to know.”

Kenkel’s previous work in animal models has shown that early intervention to supply these hormones shortly after birth prevented subsequent weight gain.

He also wants to explore elements of the energy budget, such as dietary intake, activity, temperature and fat distribution, in rodent animal models to better predict where infants born via C-section might store extra calories. He’s especially interested in whether these extra calories are stored in fats and, if so, whether this occurs in subcutaneous or visceral fat found around the body’s abdominal organs, such as the liver, stomach or intestines.

“If we find differences, that would actually be really important because, in humans, visceral fat leads to more inflammation and much worse health outcomes,” Kenkel said.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website