Arsenic and old books

Photos courtesy of Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library June 15, 2022

UD researchers discover the poisonous substance may be hiding in libraries across the world

Not just a tool for murder, arsenic was everywhere in the Victorian era. An abundant by-product of mining operations, arsenic was considered harmless in small doses, though its dangers were well known. It was sprinkled in countless products – cosmetics, toys and textiles – even in medicines and food in the mid-to-late 1800s. The era’s penchant for colorful décor led to one of the substance’s best-known uses: as a pigment in popular wallpaper patterns, especially those manufactured by William Morris, chronicled by Lucinda Hawksley in her 2016 book Bitten by Witch Fever.

It was while reading Bitten by Witch Fever that Melissa Tedone, affiliated associate professor of art conservation at the University of Delaware and conservator and lab head for the Library Materials Conservation at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library, realized the vibrant wallpaper patterns shown in the book matched the hue of a bright green book she was working on in the Winterthur library, Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste, published in 1857.

Emerald green, sometimes called Paris green or Schweinfurt green, is a pigment containing copper acetoarsenite, and its use in America and England during the Victorian era is well documented. Given the toxic elements’ ubiquity in everyday objects, some library conservationists wondered if Victorian bookcloth could also contain poisons, but they lacked the resources and equipment to test for toxic elements.

Enter UD expertise.

Tedone consulted with Rosie Grayburn, affiliated associate professor and associate scientist at Winterthur, and they agreed to act on Tedone’s suspicion about her 165-year-old book. For help, they turned to UD’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources’ Soil Testing Program.

Science and Soil

CANR’s Soil Testing Lab began in 1947 as a public service to help farmers identify optimal amounts of lime or fertilizer for their crops. Today, the lab still tests soil for farmers and home gardeners, and it also provides analytical services for researchers across campus, testing soil, water and plant samples, as well as research materials like bones, food and archeology samples. And, wildly enough, even books.

The lab confirmed dangerous levels of arsenic in Tedone’s emerald green book. And although Tedone’s suspicions were correct, the news still came as a shock. “It’s one thing to use a pigment like that in a small area in an illustration or painting, but this was the entire book just covered with it,” Tedone said.

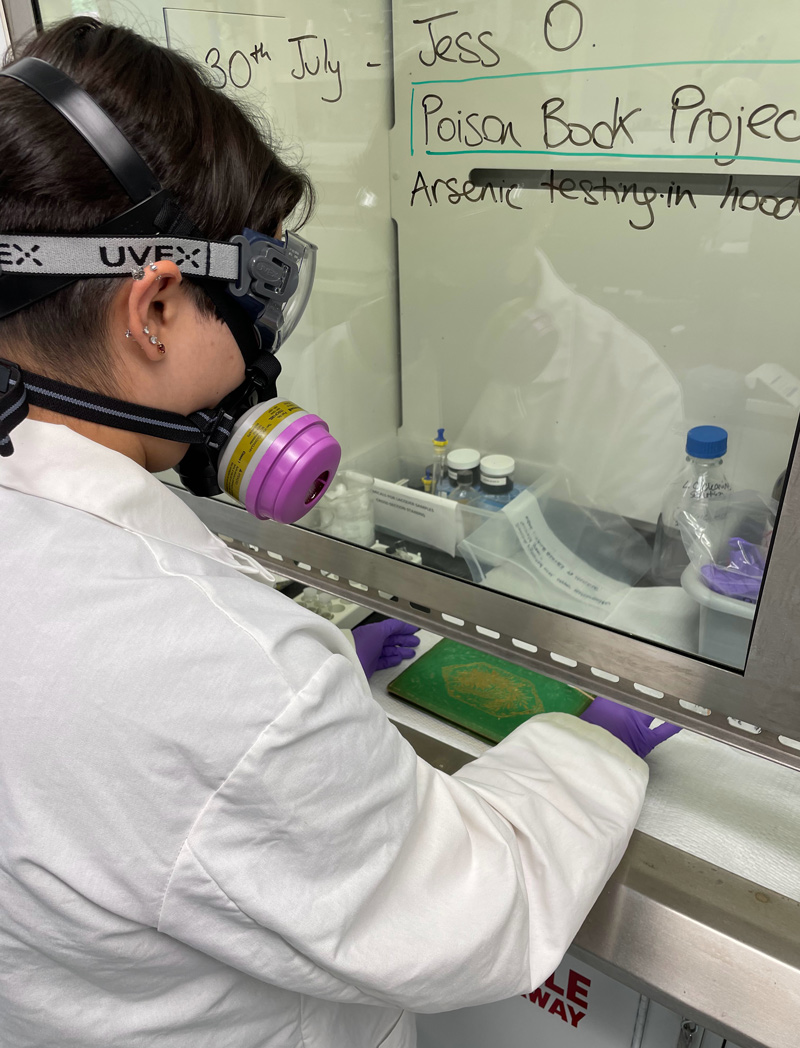

Tedone and Grayburn developed a protocol for testing other green books in the Winterthur library and created the Poison Book Project to document their progress. To date, they have tested approximately 350 green books from Winterthur’s collection, about 10% of which contained arsenic. Other institutions are adding their positive arsenical books to the database as well.

Identifying a “poison book” is a four-step process, Grayburn explained, beginning with visual identification. The green hue is so distinctive that simply looking at the book cover can determine which books should be tested further.

Next, conservationists use two standard technologies to identify chemical compounds: X-ray fluorescence and Raman spectroscopy. The first, commonly called XRF, identifies elements present in an object, such as arsenic and copper. These tests can be done easily with a hand-held tool that is as simple as using a bar scanner.

If the suspected elements are found, Raman spectroscopy provides in-depth analysis that identifies specific pigments, such as emerald green. Spectrometers are larger, non-portable machines, making them less common.

As non-destructive tools that leave the books intact, Raman and XRF are preferred methods for conservationists. The fourth step of sending samples to the Soil Lab is used very rarely, as it cannot be done without destroying the sample.

The Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC) and CANR’s Soil Testing Program provided the technologies for each step that Tedone and Grayburn needed to make the Poison Book Project successful, and there has already been significant impact in the field of library conservation. The pair is contacted weekly by colleagues around the world looking for advice on testing their own collections.

Student Impact

Working on the Poison Book Project offers art conservation students the opportunity to get real-world experience, and, as Tedone said, make a meaningful contribution to the field while still students.

Jess Ortegon, a third-year WUDPAC graduate student, worked on the project during the summer of 2021, analyzing a selection of books suspected of having chrome yellow bookcloth, a pigment that contains lead. They are currently at their third-year internship at the University of Michigan, assisting the library with analyzing books for toxic substances.

Ortegon’s experience inspired their personal research interest in the pigment vermillion, which contains mercury sulfide, and their knowledge of the analytic techniques helped Ortegon land a two-year residency with Northwestern University that begins this fall, where they will be part of analyzing 2,000 books from the university collection to identify and catalog toxic substances like emerald green, chrome yellow and vermillion.

The Poison Book Project

In contrast to the manufacturers who kept secret the process for creating toxic Victorian bookcloth, Tedone and Grayburn said they hope their research can be widely known in the field of library conservation. One goal of the Poison Book Project is to document every book that has been identified as being made with emerald green and eventually serve as a comprehensive reference for this and other toxic bookcloths.

Additionally, they formed the Bibliotoxicology Working Group, an international group of librarians, conservators, historians, cultural heritage scientists and health and safety professionals. Their goal is to create standards for identifying toxic components in books and define best practices for keeping both the materials and the people safe.

Because few conservators have access to the tools necessary to conclusively test their collections, Tedone and Grayburn created a color swatch bookmark to help people visually identify books that might be bound in emerald green bookcloth. To request a color swatch bookmark, individuals can email poisonbookproject@udel.edu with “Emerald Green Bookmark” in the subject line and their name and postal address in the body of the email.

In the meantime, the scholars share simple steps that conservationists and private collectors alike can take if they suspect they have poison books in their collections.

First, never handle the book with bare hands. Wear nitrile gloves (like those used in medical offices).

Second, place the book(s) in a zip-lock plastic bag. Food-storage bags from a grocery store are sufficient for temporary storage. For long-term storage, polyethylene bags (which can be found on library storage supply sites) provide an effective barrier and will not leach gas or plasticized colors on the book.

And, importantly, don’t panic, the team said. Much as household cleaning products are safe when used correctly, poison books are harmless if handled properly.

“It’s important to preserve these books,” Tedone said. “They have historical significance – the history of the book itself, evidence of manufacturing, for the history of trade.” Identifying emerald green bookcloth and establishing the Poison Book Project are just the next steps in library preservation.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website