The hero of happiness

October 29, 2022

“For those who do it, it’s less of a career than a lifestyle. It’s not what you do, it’s who you are. There’s a blurry line between one’s own identity and the character.”

-Robert Boudwin, BE97, the first YouDee and creator of Clutch, mascot for the Houston Rockets

It’s a strange feeling, to look in the mirror and not see yourself. Your movements and mannerisms are your own, but in a face and body so utterly different than the one you inhabit, so unlike anything anyone, anywhere, has ever seen.

You stare. You touch your cheeks with green, furry hands. You disco dance like Travolta on a Saturday night. You blow your lips and watch a rubber tongue emerge from your snout like a party horn. You move your hips from side to side, the fat, green belly swaying comically before you.

Then you walk out of the dressing room, past dozens of staffers waiting for the game to begin. Their faces burst into smiles and whoops and laughter, and you can still hear the faint echoes of their cheers as you open the doors to Section 332, Veteran’s Stadium, right behind home plate.

It’s a picture-perfect spring day, and the breeze ripples through your feathers as you run to the third-base stands, jump over railings, and feel the aluminum vibrate beneath your size 30 shoes.

Those feet carry you onward, almost of their own accord, to the nearby picnic tables, where you leap from bench to bench with the gracelessness of the flightless bird you’ve now become.

That night, your team wins. “We’re 1 and 0 with the Phanatic,” catcher Tim McCarver boasts the following morning.

Over the next 16 seasons, and in the decades beyond, you’ll follow the directive you were given that very first day in 1978 by Bill Giles, president, and later, chairman of the Philadelphia Phillies.

Brilliant and fearless, he’s the man who installed slanted tables in the Houston Astrodome to help customers feel tipsier and knew instinctively to make you “fatter, greener and with a bigger nose.”

So on opening night, you’ll tentatively open his office door and ask, “Mr. Giles, what exactly is it that you want the Phanatic to do?”

His pensive expression will worry you at first, but then he’ll break into a huge smile and calm your fears. “David, just have fun," he'll say. "If you’re not having fun, then the Phanatic won’t be funny and the fans won’t like him.”

And oh, how they do.

Their love is so palpable it feels as if they love you too, a force so beautiful and terrifying you begin to wonder if the bean counters in accounting will find someone else to be stupid for less. If you’ll lose the greatest gig of your life. If you’re more man or mascot.

But where does one end, and the other begin?

Fantastical origins

The Phanatic was a Darwin experiment gone wrong, born among the tortoises and sea lions of the Galápagos Islands and shunned by his peers as unreal and unlovable. He would eventually leave the coast of Ecuador, searching the world over for a place to call home and finding it in the City of Brotherly Love.

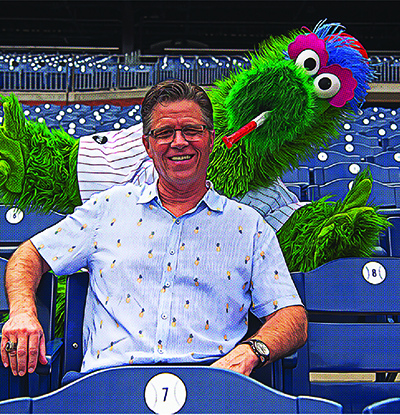

Dave Raymond, HS79, grew up in a loving family with two interchangeable homes. There was the house in Newark, where he lived a Leave it to Beaver life, and there was the University of Delaware, where his father was a coaching legend long before his 300th football win.

Hired by the Carpenter family (longtime University benefactors and owners of the Philadelphia Phillies), the late Harold R. Raymond, or Tubby, as he was known to everyone but his parents, was a man of unfailing integrity.

In the words of former player Joseph Biden, AS65, 04H: “Tubby’s notion was, you get knocked down, you get the hell up. Never complain, never explain. Work hard, play by the rules, treat people with dignity and respect. Most of all, cover your team.”

Coach Raymond was a man of mythic proportion who could move grown men to tears, making them greater than they thought they could be. His youngest son would witness such sermons in the locker room and dream of one day playing for his dad and someday coaching like him, too.

He would accomplish the former as a Delaware kicker, quickly growing his family to include 150 Sigma Phi Epsilon brothers, 16 of whom were starting players on the football team. The “SPE dogs,” as they would call themselves, “were like Animal House, but with less debauchery,” Raymond jokes now. And in a catchphrase that seems reminiscent of many a Blue Hen memory, he simply smiles of his undergraduate years and says, “I had a great time.”

His experience only improved when his father secured him an internship with the Phillies. “You never know what might happen or where it might take you,” the elder Raymond said. For good measure, he also offered his son a word of advice: “Talk less.”

A Phanatic’s tale

On April 25, 1978, Dave Raymond embarked upon a role where he couldn’t talk at all.

“When people ask me what it’s like to be the Phanatic, I tell them, ‘Imagine you have a job where you’re not just well known, but beloved. Everyone wants a picture with you. You get to go to the best parties, the biggest events. When you show up, you’re the star.’”

You’re a cross between the prototypical Philly fan (passionate, cynical, dangerously knowledgeable) and slapstick greats like Daffy Duck and the Three Stooges. You’re a dancer, an entertainer, a SPE dog. You spit-shine bald heads, buzz around on a four-wheeler, dance on the dugout, spill popcorn on opposing fans.

You terrorize LA Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda and high-five Tug McGraw. You entertain the Kennedys. You strut in costume into Studio 54, and you even ride down Broad Street on your own 18-wheel truck after the 1980 World Series win.

You wake up each morning living a dream. And then one day you stare blankly as the words escape the doctor’s lips: Malignant tumor in your mother’s brain. Stage 4 Glioblastoma. Eight months to live.

You walk onto the sidewalk, admire the autumn sun, and weep.

You think about your childhood and remember the time the Methodist pastor asked you to become an acolyte. You wanted to wear the robes and walk the aisles, but you were petrified of knocking over candles or otherwise embarrassing yourself. Your mother held you then and said, “Fear is not a good enough reason to limit yourself.”

Suzanne Heinemann was fearless. An independent woman who lost her hearing from Meniere’s Disease, she dedicated much of her life to Delaware’s deaf community. She taught you how to communicate without words, how to cook a pot roast, how to be unafraid.

But you are. And eight months later, almost to the day, you lose her. Her service is held in the same Methodist church where you once lit candles. Though you want to speak, you can’t, the words hollow and the tears irrepressible.

Father Jim Dever tells you afterwards that you showed much-needed emotion and gave fellow mourners permission to cry, and you recall the first time you met the Catholic priest, back when he asked the Phanatic to interrupt his service, and you tried to get out of it because you were again afraid of embarrassing yourself in church. “But David, this will be perfect,” Father Dever had said. “My homily is all about how life can surprise us with a curveball or two, and the Phanatic’s unanticipated visit will set that tone.”

You spend that Mother’s Day weekend golfing with your father, leaving your wife and 3-month-old son behind. They will be gone by the time you return, the curveball of their departure so swift and excruciating that the thought of now putting one foot in front of the other seems impossible.

And yet, you have a job to do. You drive to King of Prussia for a two-hour gig, zipping yourself into the fur and becoming something and someone else. You are now making other people feel good, and it makes you feel better, and you emerge from the deepest depths of your misery to understand the great philosophy your best friend, the Phillie Phanatic, has been trying to teach you: that in the face of loss, pain and devastating defeat, you can still choose fun.

The emperor of fun

The social psychologist Malcolm Gladwell has famously written of the factors that contribute to extraordinary success: luck, access, and 10,000 hours of practice. They ring true to Raymond.

“My dad snaps his fingers, and I have immediate access to the Phillies. I have all these skills I didn’t know would be useful, but they clearly had an outlet. And I’ve had well over 10,000 hours of being a professional idiot,” says Raymond, a nationally regarded keynote speaker, entrepreneur and author.

Those unique factors give him some authority to spread the Phanatic’s gospel. “When the brutality of life visits you, that is the time to choose the distraction of fun,” he says. “It sounds counterintuitive, but it’s your own intentional activities that will save you. They will rewire your brain and refresh your perspective.”

There was a time when Raymond didn’t think he would ever have a happy family life again, that he wasn’t worthy of one. And then he met Sandy Ingram, a woman who was “weak-knees pretty” and loved him despite his flaws and gave him the confidence to see himself as more than a clown. Today, his favorite vacations are the ones to visit his eldest son Kyle, in Colorado, or the ones he and Sandy take with their children, Maddie, Carly and Dylan.

When Maddie, EHD20, has a 6am sorority dance practice, he’s there, cheering her on. When Carly, HS22, came home crying because her high school softball coach never gave her a shot, Raymond reminded her to be patient, work hard and cover her team.

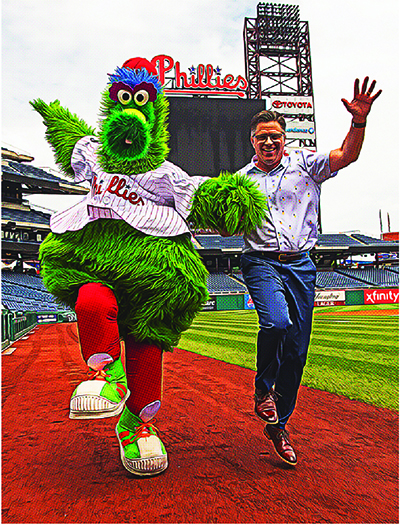

“He’s a great dad, a wonderful man,” says former Phillies owner Bill Giles. Chris Long, director of entertainment for the Phillies and the Phanatic’s unofficial mom, agrees. “He’s always so self-deprecating, but he’s an amazing father and husband."

And despite what Raymond thinks, nobody else could have originated the role he so effortlessly developed. “It’s just a shag carpet,” says Long. “But you put it on the right person, and it becomes the Phanatic—childish, funny, a little devilish.”

It’s Raymond’s orbit of outgoing, self-deprecating, kind, contagious hilarity that makes him a mascot for all mascots. And in their delightfully peculiar world, there is no greater expert.

After leaving the Phillies is 1993, he opened the Raymond Entertainment Group, a marketing and consulting firm that has created over 175 mascots and helped businesses build huggable brand extensions—along with less cuddly ones like the Flyers’ Gritty.

He has also run hundreds of mascot training camps for kids, colleges, and everyone in between.

At UD, he met YouDee’s Chris Bruce, BE02, who would later work with Raymond as a trainer and help establish an online Mascot Hall of Fame. (The idea hit them, so to speak, in 2003, after a costumed sausage was bopped in the head at Milwaukee’s Miller Park.)

Nearly 10 years later, the city of Whiting, Indiana approached Raymond Entertainment Group with a proposal to build a three-story, 25,000-square-foot children’s museum honoring the quirky creations Raymond helped pioneer.

It was a dream come true, a legacy-defining moment. But when the Mascot Hall of Fame opened this past spring, in a ribbon-cutting ceremony marked by buffoonery and hijinks, shenanigans and shimmying, the hands-down Greatest Sports Mascot of All Time was nowhere to be found. Instead, Raymond had been foiled by a flight delay.

“Years I’ve waited for this moment, and the plane had to have maintenance issues,” he told a news reporter shortly after his arrival (about an hour after the doors opened to the masses).

But he didn’t let it dampen his spirit. Doing so would go against everything Raymond so ardently believes, that when confronted by life’s great adversities and mere irritations, we have the power to choose fun. And so he photobombed a selfie with a lion in a crown, and did.

Contact Us

Have a UDaily story idea?

Contact us at ocm@udel.edu

Members of the press

Contact us at 302-831-NEWS or visit the Media Relations website